INTRODUCTION

Lithium-ion (Li-ion) batteries are an everyday essential item embedded in everyday life, found throughout the world and in almost every household or workplace in one form or another. We can find them in portable devices such as mobile phones, laptops, tablets, power banks and cordless vacuums, all the way through to electric vehicles (EVs) – scooters, buses, cars and bikes. However, their widespread use has led to a surge in fire incidents, particularly involving EVs. Recent media reports and insurance data highlight a 17% increase in Li-ion battery-related fires in New Zealand alone1. As the maritime industry embraces the global shift toward electrification, the integration of Li-ion batteries and EVs onboard vessels presents both opportunities and significant fire safety challenges. This article explores the science behind Li-ion batteries, the risks they pose, and the implications for maritime operations, drawing on recent incidents and emerging mitigation strategies.

UNDERSTANDING THE BATTERY: CONSTRUCTION AND CHEMISTRY

Li-ion batteries consist of:

- Electrodes (anode and cathode) – where Li-ions are stored during battery charging and discharge and where the electric current enters and leaves the battery.

- Electrolyte – organic solution that the Li-ions pass through but electronically insulating. This is the flammable component of a typical battery.

- Separator – A porous membrane that physically separates the electrodes from one another and allows Li-ions through.

During discharge, Li-ions flow from the negative electrode (anode) to the positive electrode (cathode). When the cell is charging, the ions flow in the opposite direction, from cathode to anode.

EV battery packs are complex assemblies of connected cells known as modules, enclosed in protective casings with integrated cooling systems and Battery Management Systems (BMS). The battery pack is typically integrated into the chassis of an EV. The battery pack enclosure not only protects the batteries from external damage and ingress of dirt or debris, but it can temporarily contain a fire in the enclosure, providing time for fire extinguishing and preventing propagation to other cars. However, for such Li-ion battery fires, the encasing also makes firefighting more difficult by preventing direct access to the battery pack itself.

The BMS monitors voltage, current, resistance and temperature of the battery, which are all vital to allowing the battery to function at its optimum potential. It is also critical for balancing the cells, which means ensuring that every single cell within each module of the battery pack charges and discharges at the same level. Cell balancing is critical to prevent over-charging or over- discharging of any single cell within the pack. Over-charging or over- discharging batteries can lead to battery failure.

The BMS also monitors the State of Charge and State of Health.

FIRE RISK AND THERMAL RUNAWAY

Li-ion batteries can fail due to:

- manufacturing defects

- Battery management

- Software faults

- Internal/External shirt circuits

- End Of Life

- Battery abuse

- Mechanical damage -This is external damage, such as dropping from a height, indentation, or punctures, etc., which can result in damage to the internal components, rendering the battery unstable

- Electrical Abuse – Over charging or over-discharging the battery. This can occur due to manufacturing faults in battery cells and ineffective monitoring and voltage by BMS

- Thermal Abuse – Subjecting the batteries to extreme temperatures or the local temperature is too high which could be due to poor battery design or manufacture, or the BMS not regulating temperature properly

Each type of battery abuse described can lead to battery failure. Mechanical abuse can cause the separator to break, causing a short circuit by contact between the two electrodes, whilst electrical abuse can lead to formation of dendrites (branches of lithium) which can pierce the separator, again resulting in short circuit. Thermal abuse at high temperatures can lead to electrolyte breakdown. The battery failure can lead to a phenomenon known as ‘thermal runaway’. Thermal runaway is the term used to describe when a reaction becomes self-accelerating; this occurrence is not exclusive to batteries. In the context of batteries, battery failure can result in exothermic (heat generating) reactions taking place, the heat generated from these reactions allow for more reactions to take place, creating a positive feedback loop. Eventually, the reaction reaches an uncontrollable, self- sustaining and self-accelerating state, i.e., thermal runaway. The time taken to reach thermal runaway can be very fast, giving little time to react, and with devastating consequences.

MARITIME INCIDENTS INVOLVING LI-ION BATTERIES

Whilst root causes are often difficult to determine due to extensive damage, several high-profile ship fires have been linked to Li-ion batteries, including:

- S-Trust (USA 2022) – Charing of Li-ion batterie son a bridge

- Felicity Ace (Atlantic, 2022) – Carrying new EV’s and ICE on board

- Fremantle Highway (Netherlands, 2023) – Carrying new EV’s and ICE on board

- Morning Midas (North pacific , 2025) – Carrying new Ev’s and ICE

Additionally, the number of Superyacht fires are on the rise. Superyachts generally carry an array of ‘toys’ onboard, typically battery powered. These can include e-scooters, e-bikes, sea bobs, drones and now electric jet skis are being introduced into the market.

CHALLENGES FOR FIREFIGHTING ON DIFFERENT TYPES OF VESSELS

Firefighting on different vessel types can present different problems. Below are some of the difficulties that can be encountered when fighting a fire on these ship types.

RO-RO AND PCTC VESSELS

Ro-Ro and PCTC ships lack transverse bulkheads which means large open spaces on each deck that allow a fire to spread quickly longitudinally as there are no subdivisions to contain the fire. The lack of subdivision also makes fire suppression more difficult. This is illustrated in the GA Plan for this vessel type, an example of which is shown below.

Essentially the subdivision of the watertight compartments makes it like an oven, which is illustrated in in these vessel types. the thermal image. Whilst this was not an EV fire, it demonstrates how fire can spread longitudinally.

Additionally, excessive amounts of water cannot be used for firefighting, as too much water on an open deck could lead to free surface effect and stability issues. Due to the tightly packed cargo stow, there can also be physical challenges for seafarers fighting these fires as there is very limited access between vehicles. The minimal space between vehicle rows also means that it is difficult for wearing a breathing apparatus (BA) set. There is the added uncertainty of what vehicle types are stowed on deck. Locating the origin and source of the fire can be difficult in the stow, as well as recognising if the vehicle is electric, hybrid or ICE. Currently, there is no requirement for identifiers to be placed on the cars to distinguish between electric, hybrid, or ICE vehicles.

In an emergency, a typical muster on a vessel takes between 8-12 minutes. The crew then need to get kitted up and access the fire for firefighting. A normal BA set has around 20 minutes of air, and it could take a fire team 5-10 minutes to reach the required car; the fire team must also factor in having enough time to safely get back out. Taking into account the time taken to enter and leave the compartment the crew is likely to have a very short period to fire fight. The recommended firefighting method for a Li-ion battery fire is the use of a fire blanket weighing 20-40kg. Practically, this will not be easy for a fire team to handle and use in a tight stow, particularly whilst wearing BA.

CONTAINER SHIPS

Container ships present their own challenges. Large quantities of small parcels of cargo are carried in security sealed and contained units. Containers are stowed both above deck and in the holds, which can give difficulty in locating the origin and source of the fire

Stowage of containers (with EVs inside) in the hold can be beneficial as the space could be flooded with CO2, but fighting a fire within a specific container could be difficult. Stowage on deck can be beneficial as the container can be situated away from the accommodation but could still be difficult to access. Stowage in the upper tier locations on deck can present challenges in the event of a fire, unless the ship is fitted with hi-rise monitors/nozzles to apply large quantities of water direct to the burning container. Due to the nature of the stow, it can be difficult to access specific containers. Mis- declared cargo is also an issue that can affect firefighting and emergency situations.

ADDITIONAL FIREFIGHTING CONSIDERATIONS

As previously discussed, the batteries are located in the chassis of the vehicle. Approaching can therefore be difficult for any firefighting team as their pathway can be blocked by flames. In addition, significantly more water is required for fighting an EV fire compared to a combustion engine vehicle. For example, 30,000 gallons of water over 4 hours are estimated to be required for an EV fire, instead of 500-1,000 gallons over 30 minutes for a combustion engine car. Large quantities of water are not suitable for use on ships, particularly on large open surfaces as previously discussed.

EV fires also generate much higher temperatures than an ICE fire with a sustained flame, which can be difficult to ‘knock-down’. Re-ignition can also occur, in some cases, a considerable time after the fire has been extinguished. Methods for fighting a fire involving Li-ion batteries remain under review, with new technologies being researched and developed. There is currently no definitive answer for how best to tackle an EV fire.

LESSONS FROM RECENT INCIDENTS

Brookes Bell have attended fire incidents and casualties that have involved both the carriage of Li-ion batteries and EVs. Following these attendances, additional challenges came to light which may not be fully appreciated by the wider industry, and particularly the seafarers at the front line. Firstly, as a consequence of thermal runaway, there is a possibility of flammable gases collecting in enclosed head spaces that the ship’s crew may not be aware of. On a recent case we attended, there was evidence of a vapour cloud explosion beneath the top canopy deck, lifting it 2.5 metres across 100 metres length. As a result, the crew were unable to access the lifeboats on this deck. Additionally, the fire and foam mains also ran the length of this deck and had been buckled following the explosion. Following the fire, many of the car carcasses were unrecognisable. Aluminium has a melting point of 660°C; however, car manufacturers have reported that tests involving EV fires can reach temperatures in excess of 2,000°C. As a result of the extreme temperatures, heat can also transfer downwards, not only upwards, burning container floors or melting aluminium structures which have the potential to block bilges and scuppers. The photographs show the stalagmites created by molten aluminium on a recent attendance.

Ship designs may also need to be reconsidered. Based on our experience, access into certain spaces may not be suitable to safely exit in an emergency involving EVs. For instance, open stairwells will pass through car decks, meaning that crew would have to move through a fire zone that could potentially be filled with toxic gases.

On this note, should further investigation also be given into Personal Protective Equipment (PPE) for ship’s crew? If crew are on deck awaiting rescue or whilst accessing the lifeboats, should a full-face mask be worn, such as the PPE that are being used by personnel attending in the aftermath of responding to a Li-ion fire? Face masks could be held on the bridge or within the accommodation of ships for personnel to use in the event of evacuation from a ship that is on fire. As well as the toxic and flammable gases emitted during thermal runaway, the dust and other matter created by the fire can also be toxic and harmful. Another challenge is the potential that the firefighting water could short circuit batteries in stowage. During our attendance, when moving cars that had been flooded with firefighting water, a short circuit took place as the car was being removed from the vessel.

Risk Mitigation Strategies and Future Directions

BATTERY ENERGY STORAGE SYSTEMS (BESS)

More vessels are starting to ship BESS or ‘Megapacks’ which can present additional risks. This type of cargo is typically high value with a high energy density. Stowage needs to be considered carefully. Tight stowage complicates isolation during incidents, as access can be restricted and the fire can propagate between units. However, if not stowed as a block stow, the units need to be sufficiently secured individually for a sea passage. Additionally, manufacturer guidance may not always be compatible with maritime conditions. The stowage and securing guidance for Megapacks (Tesla) for instance, states that there should be no more than 5 degrees tilt. This cannot be guaranteed on a vessel at sea.

TECHNOLOGICAL INNOVATIONS

Li-ion battery research is still a growing research area. With new designs and innovation, the industry is always looking at ways to improve battery quality, safety and performance and durability. With this, numerous modifications are currently being researched; some examples are provided below:

- Electrolyte modifications (e.g solid-state, non-flammable electrolytes)

- Modification of other battery components (e.g separator, electrode coatings)

- Battery pack level innovations (improved cooling and pressure relief systems)

VESSEL DESIGN

Vessel design is also currently being reconsidered. Purpose built vessels for shipping EVs and Li-ion batteries are in discussion. One potential design is to increase the number of subdivisions and compartments, as there is more chance to isolate a potential fire or incident within these smaller compartments.

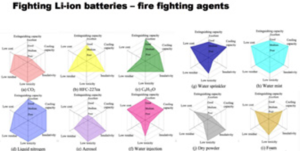

FIRE DETECTION

Additionally, fire detection systems are being adapted and modified. For instance, the Li-ion Tamer detects catastrophic battery failures early. The Li-ion Tamer is a plug-and-play rack system that improves safety by sensing the off-gassing that precedes thermal runaway battery failures much earlier than smoke, or traditional gas detection systems would. Li-ion Tamers work at the second stage of battery failure: the interval between off-gas generation and smoke to stop thermal runaway before it gets started. The most effective firefighting medium for Li-ion fires is still being investigated. The figure below2 shows a range of fire fighting agents and how effective they are against Li- ion batteries. Generally, firefighting mediums work by isolating, smothering, cooling, or chemically suppressing fires. One factor to consider for Li-ion battery fires is the re-ignition aspect; even after cooling to room temperature, the probability of re-ignition still exists. The potential environmental impacts of the firefighting agent post-fire must also be considered.

RESEARCH

Various working groups and organisations are looking into options for tackling EV fires. Industry groups are developing documents designed to assist industry and ships’ crews in how to deal with Li-ion fires, with several white papers being produced. Technology is constantly evolving; and continuous monitoring of developments is required.

CONCLUSION

The maritime industry must adapt rapidly to the evolving risks posed by Li-ion batteries and EVs. Through a combination of scientific innovation, vessel design, and operational preparedness, we can navigate these challenges and ensure safer seas.

By Karley Smith and Yvonne Tung, Brookes Bell